Shelf Talks #11: Suzanne

Shelf Talks is a series of interviews in which writer and librarian Oleg Kagan asks interesting people questions inspired by the contents of their bookshelves. Suzanne Stauffer is a retired librarian, professor emerita of Library & Information Science, and author currently living in Baton Rouge, but moving to Albuquerque in July, 2024. She is a member of the SouthWest Writers and the New Mexico Writers. Her historical mystery, Fried Chicken Castañeda, set in Las Vegas, New Mexico in1929, will be published in Spring 2024 by Artemisia Publishing. You can read more from Suzanne at her blog. In this interview, we explore the Wild West from a unique angle: food. Suzanne describes how meals differed between everyday settlers focused on survival and the wealthy elite who enjoyed fine dining options. The rise of celebrity chefs on trains like the Santa Fe is also discussed. Suzanne then dives into her writing process, revealing the challenges and joys of weaving historical accuracy with fictional narratives. She emphasizes the importance of detail while ensuring the story remains believable and engaging for readers.

OLEG: In perusing your books, I see various historic culinary titles primarily focused on the Old Southwest. Were there gourmands or "foodies", and the consequent celebrity chefs, in the wild west? If so, how did it compare to being a foodie now?

SUZANNE: Great question -- and not one I was expecting. As with so much in life, it really depends on exactly when and where. In the early days of homesteaders and pioneers, not only were people just struggling to find enough to eat, there weren't any cities, so no fine-dining restaurants. A local woman might have been known for her bread or pies or whatever, and men did want a wife who was a good home cook, but nothing fancy, nothing gourmet. No time and no ingredients. They could only cook what they could grow or gather or hunt, or buy at the general store once there was one. Of course, some of our current “foodie” trends -- sourdough bread, in particular -- would have been considered "plain home cooking" at that time and place.

Interest in food as food, not as a necessity, has always distinguished the elite from the working class. After the Gold Rush, when San Francisco had become a wealthy city, the upper-classes had the time and money to indulge in the appreciation of food and drink. It's not my area of expertise, so I can't name restaurants and chefs, but I do have the sense that there were local celebrity chefs, although it may have been as "the chef at the X restaurant," rather than by name. Chinese immigrants added to the culinary landscape and certain restaurants became known for their food.

After the Civil War, with the building of the transcontinental railroad, as cities were established along the routes -- Kansas City, Denver and Salt Lake City spring to mind -- hotels and restaurants gradually developed to cater to the first-class passenger and the quality of the food became important. The passengers might take memories of specific dishes back home with them, but in the absence of a national mass media, a chef's celebrity was primarily local, among the wealthy of the city.

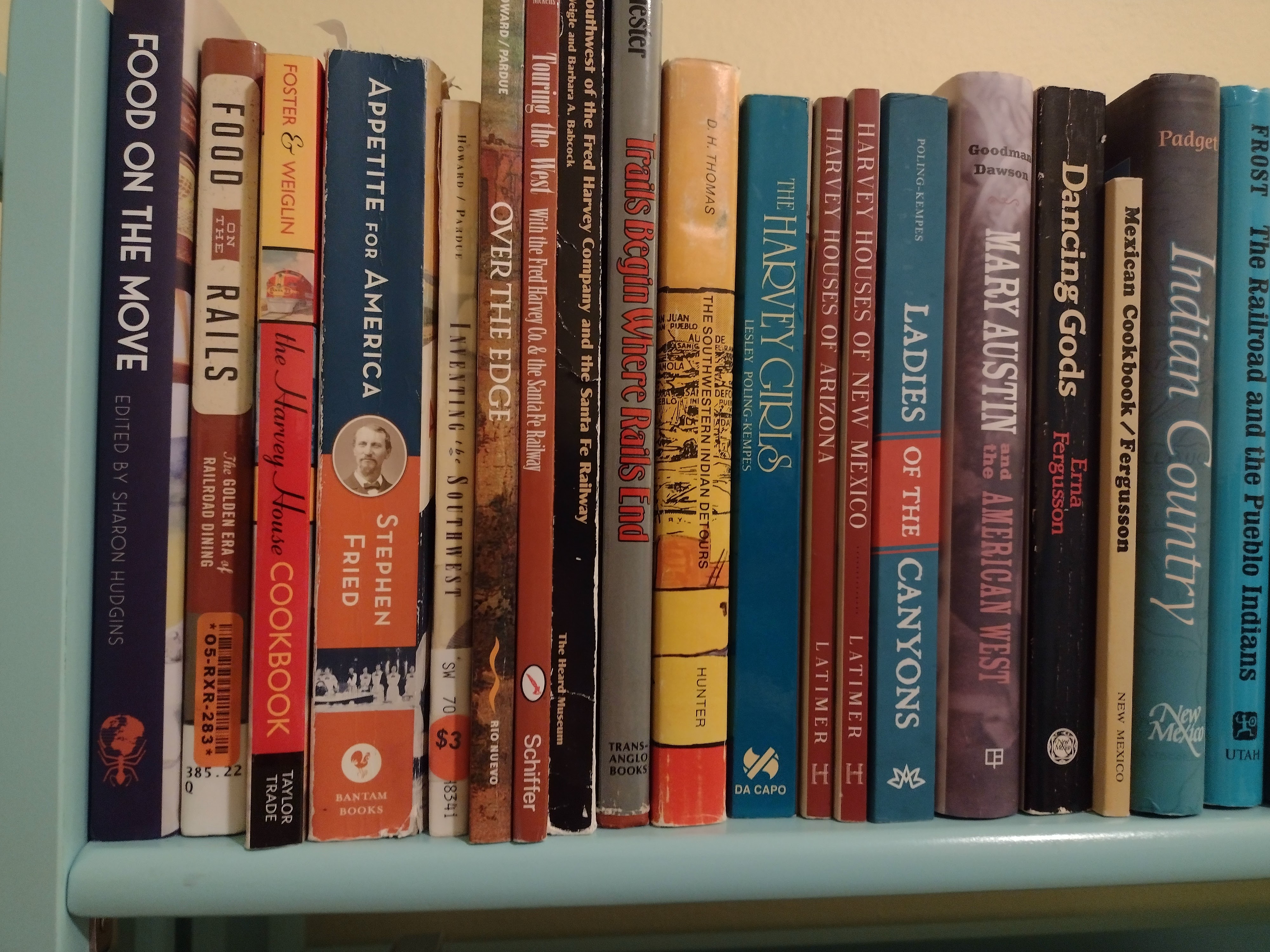

Two of the titles on my shelves are about the food served on the passenger trains. The other two are about the food of the Fred Harvey Corporation, which had an exclusive contract for the dining cars on the Santa Fe railroad and the restaurants and hotels at Santa Fe railroad stations beginning in the second half of the 19th century. They were renowned for the quality of the food, which owed as much to the fact that the railroad delivered fresh ingredients daily as it did to the preparation. People traveled on the Santa Fe rather than a competitor because of the food, but it was only after WWI that individual chefs began to be recognized. The first was Konrad Allgaier of La Fonda in Santa Fe, NM. He had been a chef to Kaiser Wilhelm at one point and started his career in this country as a chef on the Santa Fe Chief. He moved to La Fonda in 1930 and became Santa Fe's first "celebrity chef." He was interviewed in national magazines and shared the recipe for his signature dish, Pollo Lucrecio. But that's well after the "wild west" days.

So, the short answer is not really. Very few people had the money and the leisure. The average farmer, rancher, homesteader was just trying to keep body and soul together. Only the elite who lived in larger population centers such as San Francisco had the money and leisure and only in those areas did chefs have access to the diversity of ingredients necessary. While chefs may have earned celebrity, it was primarily local in the days before national mass media.

OLEG: You mentioned that people chose to travel on the Santa Fe due to the quality of the food. I wouldn't have expected that as a differentiating factor on the rails, but of course it makes sense, especially if a trip takes more than a few hours. Are there other unexpected distinctions among rail companies that you found fascinating in the course of your research?

SUZANNE: Nearly all long-distance travel was by train until the 1950s and the building of the interstate system under Eisenhower, so food was a major consideration, as were sleeping arrangements. While long distance trains all had Pullman cars, only on the Santa Fe could you count on sleeping at a Harvey House at your destination. There weren't many (any?) other chain hotels or restaurants in the first half of the 20th century, so you never knew what you'd find when you got where you were going, especially if it wasn't a major city. I know that Fred Harvey was the first of both. I'm not sure when others followed.

My research is into the Fred Harvey Corporation more than railroads, so what I know of railroads is more or less restricted to Santa Fe. It was the only railroad that ran from Chicago to Los Angeles. There are two more differences that I know of. One is that the Santa Fe railroad was recognized for the quality of its service, some of which was due to the Harvey employees in the dining cars, and the "gentility" of its conductors and other personnel. This was credited to the series of Reading Rooms that the SFRR built along its routes. I could go on at length about them -- and have in a published article -- but I'll try to summarize.

They were modeled on the Railroad YMCAs, but were owned and operated by the Santa Fe at their stations in the Southwest. They provided libraries of books and periodicals, as well as sleeping rooms, and a regular series of entertainers/entertainment, including concerts, Shakespeare plays, and literary recitations. The purpose was to keep men out of saloons -- drunk railroad men cause accidents -- and gambling houses -- men in jail for non-payment of gambling debts aren't available to work -- and brothels, because they also wanted to attract settled, stable married men with families to those isolated stations. An unexpected positive consequence was that the Santa Fe employees gained the reputation of being cultured and genteel. This was important because women, often with their children, were starting to travel without a male escort. One Santa Fe employee reported that a man told him that he felt safe sending his wife and children alone (i.e., without him) on the Santa Fe because employees who read "good books" and attended those kinds of entertainments were obviously of a superior moral character.

The other difference, which is really my area of research, was the Southwestern Indian Detours of the Fred Harvey Corporation. These were a collaboration between Harvey and the Santa Fe. They began in 1926 and initially were one- and two-hour sightseeing car trips -- the car was part of the attraction in 1926 -- meant to fill the time between trains (layovers) at Santa Fe stations in New Mexico and later Arizona, hence the idea of a "detour." Soon they expanded to two-, three- and even nine-day excursions that were a destination in themselves. They continued through the Great Depression, because they catered to those in the upper-income brackets, but kind of fizzled out by WWII. They were led by women tour guides called "Couriers," who are generally thought to be the model for airline stewardesses -- and they are my real interest and the subject of my fiction.

I'll also be presenting on the Santa Fe Reading Rooms at this year's Fred Harvey Weekend at the La Fonda in Santa Fe. More details on request.

OLEG: I've learned a whole lot in just your past few responses, and it sounds like discovering details about this milieu is a particular passion of yours. So much so that you do it in parallel roles as a historian and writer of fiction. I wonder if it would be possible to get some insight on how these two roles interact within you. Obviously, a scholar requires a higher threshold of evidence when synthesizing elements of the past, so my question would be: Does your academic side ever sound alarms when you are forced to make assumptions as a fiction writer? Do you ever find yourself saying "Well, I'm not sure if that's exactly how it was, but we need it for the plot"?

SUZANNE: The short answer is "Absolutely! All the time!" So much so that I've included an Author's Note to my fiction with the accurate history, along with links and suggested readings. Yes, seriously. Although, I generally am saying, "I know that's not exactly how it was, but ... I need it for the plot and it's close enough so that no one else will know." And then someone in my writer's group turns out to be an enthusiast in that very specialized area! I use my reference books, of course, but I also spend hours combing through the Internet for details about everything from clothing colors to drinks to dances to slang terms. For example, I'm starting to plan the third novel in the series and I want to set it on Route 66 in Albuquerque. I haven't been able to identify a motel that was open in 1929, but I have found one that opened in 1933. Ultimately, I had to decide that it's close enough. What matters is that there were motels on North 4th Street in 1929 and the KiMo theater opened in 1927. Given that the KiMo is still in operation, I don't think I'd have monkeyed with that. Too many people would know. I also found a cafe that had opened by 1929, but if I hadn't, I'd either have used one that opened relatively soon afterward or just called it a "cafe" or a "diner," which is what I did with the speakeasy in my current novel. I just called it "the speakeasy." And the band was "the band." The songs and dances were authentic, though.

On the other hand, I avoid anachronisms. There were cafes and diners in Albuquerque in 1929, just as there were speakeasies. I wouldn't include an Internet cafe or a McDonald's. I've even researched the history of toilet paper (it was first marketed on a roll in 1890). Slang can be difficult, both terms that were used and terms that were not. Certain common terms and idioms today that we don't even think about were not in use in 1929. My writer's group is good about picking up on those. I used the phrase "good ol' boy," but while it was in use in 1929, it was not used in the same way we use it today -- and wasn't used outside of the South. So, I changed it to "gladhander." I try to remain faithful to the attitudes toward race, gender, religion, etc., but I don't use offensive terms or slurs, and I try to include a variety of accurate attitudes. Everyone didn't have the same attitudes then anymore than they do today. However, the men in my books stand up when a woman enters the room, they hold her chair and her coat, they open doors, they offer her their arm when walking together (one man in my writer's group thought that meant that they were "involved"), they walk on the street side of the sidewalk. The women, when they wear gloves (they all didn't by 1929), remove them before eating or drinking. Everyone wears a hat.

Part of the fun of writing and reading historical fiction is immersing yourself in that time and place. Anachronisms destroy that fantasy so I avoid them as much as possible. When I tweak, I do it as subtly as possible, in ways that don't smack the reader in the face. Although, I have found that people today have some inaccurate ideas about the Interwar Period and some of my accuracies do smack them in the face, such as the acceptance/tolerance of homosexuality by younger people. Also, young women painting pictures on their knees.

OLEG: That makes sense, I would think that maintaining the fantasy is of utmost importance to writers of historical fiction since obvious errors would be jarring to readers, like breaking the fourth wall in the middle of a dramatic scene in the theatre. It's a blessing, then, to have an eagle-eyed writers group to keep you honest and, it seems, provide added expertise!

Speaking of the benefit of multiple perspectives, I want to jump genres to mystery since I believe that your books would fit into the cozy mystery niche. But really, my question is about writing mysteries in general. In composing a story where knowledge gaps play a crucial role, providing motivation to the characters but also suspense or dramatic irony for the reader, in what ways do you take special care to keep track of who knows what? It feels overwhelming to me thinking about keeping secrets from the characters, the reader, and even (subconsciously, I suppose) yourself as you sculpt the scenes. How do you keep the jig from falling apart too early?

SUZANNE: I've really had to think about this question. I think it's less a case of keeping secrets than it is of making sure that all of the pieces are in place so that the picture comes together at the end. Even in other genres, it is rare that any one character knows everything and even less common for all characters to know everything. In all genres, the tension comes from the main characters and the reader not knowing something. In romance, the question is whether it's true love. In thrillers, it's how the main character will escape and/or survive. In science fiction and fantasy, it's as much from the reader slowly learning what this new world is like as it is from the plot, which generally involves some kind of hero quest. In Westerns, we know that the good guys will eventually win, but we don't know exactly how -- and sometimes we don't know who the good guys are until late in the book.

In terms of my works, the mystery aspect of the first two (I just finished the second one -- it's in revision now) is not terribly complicated, and no one knows anything, except for the perpetrators. The mystery is really secondary to the character development in those. Also, they are something of a parody of the "amateur sleuth" genre, in that most of her deductions are wrong. That stems from my reading of so many of them over the past 5 decades and often finding the leaps of logic tenuous at best, and the conclusions unbelievable. Also, the police do not ask for her assistance or reveal confidential information. The third volume is going to be a more traditional mystery format, in part because I want to challenge myself in just the ways you describe and in part because I don't want to fall into writing to a formula. She still won't serve as an "unofficial consultant" for the police, though. So, I will have to drop a lot more clues and red herrings in this one! I will have to play fair with the reader, which is the more difficult challenge -- provide all of the necessary information, but don't make it obvious, and mix it up with a lot of irrelevant and misleading information. And at the same time, provide enough information for the reader to identify the red herrings. Now that I think about it, it's like creating a logic puzzle, and I love solving them!

Getting back to my works, even though the mystery is fairly straightforward, I had to get the timeline correct and make sure that people were in the places that they were supposed to be when they were supposed to be there to learn what they (and the reader) were supposed to learn. I'm fairly old-school, in that I draw diagrams, timelines, flow charts, etc. on paper. Even with all that, the main character in a short story I just finished could not have known what she knows at the time that she knew it. No one knew it, because it hadn't happened yet. So, I had to revise the middle section. Back in the day when I took creative writing, in college, we didn't have word processors. Mistakes like that meant retyping the entire story!

Mistakes such as that put me in good company, though. I'm just going to quote Wikipedia, "Midway through filming [The Big Sleep], Hawks and the cast realized that they did not know whether the chauffeur Owen Taylor had killed himself or was murdered. A cable was sent to Chandler, who told his friend Jamie Hamilton in a March 21, 1949 letter: "They sent me a wire ... asking me, and dammit I didn't know either."

OLEG: Looking back at my questions, it turns out that I ended up asking practically nothing about your books! I guess I'll continue that trend in the final question. Lifting our scope even higher when it comes to time, hindsight, and autobiography: Did you expect, say, twenty years ago or even forty years ago that you would have completed two historical mystery novels and would be working on your third? Did you always see yourself as a writer?

SUZANNE: Again, short answer, yes. I remember writing dreadful little quatrains when I was in elementary school. Of course, I thought that they were high art at the time. I may have written short stories; I don't remember, but I suspect that I did. I used to make up stories to tell my younger siblings. I took creative writing in junior high school and won a short story contest. I began college as an English major and took creative writing again as an undergraduate. I belonged to a writer's group when I was living and working in New York City, after I got my master's in library science, and I wrote Big Valley fanfiction online as an outlet when I was a doctoral student at UCLA. Writing novels was always part of my retirement plan -- which begins today (May 19), btw. The only thing that has surprised me is that I started on them before I retired, but I did not anticipate a global pandemic and lockdown. I remember the day I started my first novel. I had finished reading a cozy, and was left very much with the feeling that "I could do better than this." I said to my husband, "I'm going to start that novel I've been talking about right now. I'm tired of putting it off."

I don't restrict that answer to writing fiction. Non-fiction writing requires many of the same technical skills as fiction and also requires that you develop your own voice and tell your own stories (regardless of what "Reviewer Number Two" thinks). I began writing research papers in high school, and continued to do so through my undergraduate and graduate studies, culminating with my dissertation, which was a history of the establishment of public libraries in Utah. It included historical narrative and biographical sketches that wove together the more objective names, dates, and places into a coherent story. As a faculty member, I've written about twenty or so historical research papers and edited and contributed to a published book. In every case, there's a beginning, a middle, and an end. It's set in a specific time and place and includes relationships among specific individuals as well as groups of people.

Every story, whether fiction or non-fiction, attempts to convey a message to the reader and to persuade the reader. Historical non-fiction requires a background and context, just as historical fiction does. It has to follow a logical sequence of events -- not necessarily chronological -- and it has to bring everything together at the end, just as historical fiction does. Now that I think about it, historical non-fiction is very often attempting to solve a mystery. In my work, it hasn't been a murder mystery, but rather the mystery of who established this public library and how and why and what impact did it have on the community. It involves investigating who the various individuals and groups were, what their motives were, how they related to each other, whether anything was going on behind the scenes, who benefited ... the primary difference now is that I get to make up all of this stuff rather than digging through historical records!

Thank you for this opportunity. It's been fun and enlightening!

OLEG: Thank you, Suzanne! Best of luck with your forthcoming novel and congratulations on your retirement!